Flax

| Flax | |

|---|---|

|

|

| The flax plant | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Linaceae |

| Genus: | Linum |

| Species: | L. usitatissimum |

| Binomial name | |

| Linum usitatissimum Linnaeus. |

|

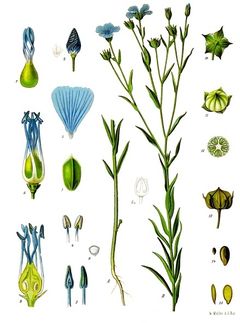

Flax (also known as common flax or linseed) (binomial name: Linum usitatissimum) is a member of the genus Linum in the family Linaceae. It is native to the region extending from the eastern Mediterranean to India and was probably first domesticated in the Fertile Crescent. It is known as Agasi/Akshi in Kannada, जवस (Jawas/Javas) or अळशी (Alashi) in Marathi and तीसी (Tisi) in Hindi, in Telugu it is called అవిశలు (ousahalu).[1] Flax was extensively cultivated in ancient Ethiopia and ancient Egypt.[2] In a prehistoric cave in the Republic of Georgia, dyed flax fibers have been found that date to 30,000 BC.[3][4] New Zealand flax is not related to flax but was named after it, as both plants are used to produce fibers.

Flax is an erect annual plant growing to 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) tall, with slender stems. The leaves are glaucous green, slender lanceolate, 20–40 mm long and 3 mm broad. The flowers are pure pale blue, 15–25 mm diameter, with five petals; they can also be bright red. The fruit is a round, dry capsule 5–9 mm diameter, containing several glossy brown seeds shaped like an apple pip, 4–7 mm long.

In addition to referring to the plant itself, the word "flax" may refer to the unspun fibers of the flax plant.

Contents |

Uses

Flax is grown both for its seeds and for its fibers. Various parts of the plant have been used to make fabric, dye, paper, medicines, fishing nets, hair gels, and soap. It is also grown as an ornamental plant in gardens.

Flax seed

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 2,234 kJ (534 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 28.88 g |

| Sugars | 1.55 g |

| Dietary fiber | 27.3 g |

| Fat | 42.16 g |

| Protein | 18.29 g |

| Thiamine (Vit. B1) | 1.644 mg (126%) |

| Riboflavin (Vit. B2) | 0.161 mg (11%) |

| Niacin (Vit. B3) | 3.08 mg (21%) |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 0.985 mg (20%) |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.473 mg (36%) |

| Folate (Vit. B9) | 0 μg (0%) |

| Vitamin C | 0.6 mg (1%) |

| Calcium | 255 mg (26%) |

| Iron | 5.73 mg (46%) |

| Magnesium | 392 mg (106%) |

| Phosphorus | 642 mg (92%) |

| Potassium | 813 mg (17%) |

| Zinc | 4.34 mg (43%) |

| Percentages are relative to US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient database |

|

Flax seeds come in two basic varieties: (1) brown; and (2) yellow or golden. Most types have similar nutritional characteristics and equal amounts of short-chain omega-3 fatty acids. The exception is a type of yellow flax called solin (trade name Linola), which has a completely different oil profile and is very low in omega-3 FAs. Although brown flax can be consumed as readily as yellow, and has been for thousands of years, it is better known as an ingredient in paints, fiber and cattle feed. Flax seeds produce a vegetable oil known as flaxseed or linseed oil, which is one of the oldest commercial oils, and solvent-processed flax seed oil has been used for centuries as a drying oil in painting and varnishing.

One hundred grams of ground flax seed supplies about 450 kilocalories, 41 grams of fat, 28 grams of fiber, and 20 grams of protein.[5]

Flax seed sprouts are edible, with a slightly spicy flavor. Excessive consumption of flax seeds with inadequate water can cause bowel obstruction.[6] Flaxseed is called 'Tisi' in northern India, particularly in the Bihar region. Roasted 'Tisi' is powdered and eaten with boiled rice, a little water, and a little salt since ancient times in the villages.

Flax seeds are chemically stable while whole, and milled flax seed can be stored at least 4 months at room temperature with minimal or no changes in taste, smell, or chemical markers of rancidity, which can start with its seed coat becoming bitter. Ground flaxseed can go rancid at room temperature in as little as one week.[7] Even after storage under conditions similar to those found in commercial bakeries, trained sensory panelists could not detect differences between bread made with freshly ground flax and bread made with ground flax stored for 4 months at room temperature. [8] Ground flax is remarkably stable to oxidation when stored for 9 months at room temperature [9] and for 20 months at ambient temperatures under warehouse conditions [8] Refrigeration and storage in sealed containers will keep ground flax from becoming rancid for a longer period.

Nutrients and clinical research

Flax seeds contain high levels of dietary fiber including lignans, an abundance of micronutrients and omega-3 fatty acids (table). Flax seeds may lower cholesterol levels, especially in women.[10] Initial studies suggest that flax seeds taken in the diet may benefit individuals with certain types of breast[11][12] and prostate cancers.[13] A study done at Duke suggests that flaxseed may stunt the growth of prostate tumors,[14] although a meta-analysis found the evidence on this point to be inconclusive.[15] Flax may also lessen the severity of diabetes by stabilizing blood-sugar levels.[16] There is some support for the use of flax seed as a laxative due to its dietary fiber content[6] though excessive consumption without liquid can result in intestinal blockage.[17] Consuming large amounts of flax seed may impair the effectiveness of certain oral medications, due to its fiber content,[17] and may have adverse effects due to its content of neurotoxic cyanogen glycosides and immunosuppressive cyclic nonapeptides.[18]

Flax fibers

Flax fibers are amongst the oldest fiber crops in the world. The use of flax for the production of linen goes back at least to ancient Egyptian times. Dyed flax fibers found in a cave in Dzudzuana (prehistoric Georgia) have been dated to 30,000 years ago.[19] Pictures on tombs and temple walls at Thebes depict flowering flax plants. The use of flax fiber in the manufacturing of cloth in northern Europe dates back to Neolithic times. In North America, flax was introduced by the Puritans. Currently most flax produced in the USA and Canada are seed flax types for the production of linseed oil or flax seeds for human nutrition.

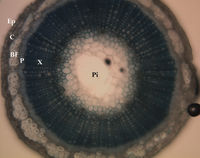

Flax fiber is extracted from the bast or skin of the stem of the flax plant. Flax fiber is soft, lustrous and flexible; bundles of fiber have the appearance of blonde hair, hence the description "flaxen". It is stronger than cotton fiber but less elastic. The best grades are used for linen fabrics such as damasks, lace and sheeting. Coarser grades are used for the manufacturing of twine and rope. Flax fiber is also a raw material for the high-quality paper industry for the use of printed banknotes and rolling paper for cigarettes and tea bags. Flax mills for spinning flaxen yarn were invented by John Kendrew and Thomas Porthouse of Darlington in 1787.[20]

Cultivation

The significant linseed producing countries are Canada (~34%), China (~25.5%) and India (~9%), though there is also production in USA (~8%), Ethiopia (~3.5%) and throughout Europe. In the United States, three states, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota, raise nearly 100% of this plant.

| Top ten linseed producers — 2007 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Production (metric tons) | Footnote | ||

| 633,500 | ||||

| 480,000 | * | |||

| 167,000 | ||||

| 149,963 | ||||

| 67,000 | * | |||

| 50,000 | F | |||

| 47,490 | ||||

| 45,000 | * | |||

| 41,000 | F | |||

| 34,000 | ||||

| World | 1,875,018 | A | ||

| No symbol = official figure, P = official figure, F = FAO estimate, * = Unofficial/Semi-official/mirror data, C = Calculated figure A = Aggregate (may include official, semi-official or estimates); |

||||

The soils most suitable for flax, besides the alluvial kind, are deep loams, and containing a large proportion of organic matter. Heavy clays are unsuitable, as are soils of a gravelly or dry sandy nature. Farming flax requires few fertilizers or pesticides. Within 8 weeks of sowing, the plant will reach 10–15 cm in height, and will grow several centimeters per day under its optimal growth conditions, reaching 70–80 cm within fifteen days.

Diseases

Includes pest problems

Maturation

Flax is harvested for fiber production after approximately 100 days, or a month after the plant flowers and two weeks after the seed capsules form. The base of the plant will begin to turn yellow. If the plant is still green the seed will not be useful, and the fiber will be underdeveloped. The fiber degrades once the plant is brown.

Harvesting methods

There are two ways to harvest flax, one involving mechanized equipment (combines), and a second method, more manual and targeted towards maximizing the fiber length.

Mechanical

The mature plant is cut with mowing equipment, similar to hay harvesting, and raked into windrows. When dried sufficiently, a combine then harvests the seeds similar to wheat or oat harvesting. The amount of weeds in the straw affects its marketability, and this coupled with market prices determined whether the farmer chose to harvest the flax straw. If the flax was not harvested, it was typically burned, since the straw stalk is quite tough and decomposes slowly (i.e., not in a single season), and still being somewhat in a windrow from the harvesting process, the straw would often clog up tillage and planting equipment. It was common, in the flax growing regions of western Minnesota, to see the harvested flax straw (square) bale stacks start appearing every July, the size of some stacks being estimated at 10-15 yards wide by 50 or more yards long, and as tall as a two-story house.

Manual

The mature plant is pulled up with the roots (not cut), so as to maximize the fiber length. After this, the flax is allowed to dry, the seeds are removed, and is then retted. Dependent upon climatic conditions, characteristics of the sown flax and fields, the flax remains on the ground between two weeks and two months for retting. As a result of alternating rain and the sun, an enzymatic action degrades the pectins which bind fibers to the straw. The farmers turn over the straw during retting to evenly rett the stalks. When the straw is retted and sufficiently dry, it is rolled up. It will then be stored by farmers before scutching to extract fibers.

Flax grown for seed is allowed to mature until the seed capsules are yellow and just starting to split; it is then harvested by combine harvester and dried to extract the seed.

Threshing flax

Threshing is the process of removing the seeds from the rest of the plant. As noted above in the Mechanical section, the threshing could be done in the field by a machine, or in another process, a description of which follows:

The process is divided into two parts: the first part is intended for the farmer, or flax-grower, to bring the flax into a fit state for general or common purposes. This is performed by three machines: one for threshing out the seed, one for breaking and separating the straw (stem) from the fiber, and one for further separating the broken straw and matter from the fiber. In some cases the farmers thrash out the seed in their own mill and therefore, in such cases, the first machine will be unnecessary.

The second part of the process is intended for the manufacturer to bring the flax into a state for the very finest purposes, such as lace, cambric, damask, and very fine linen. This second part is performed by the refining machine only.

The threshing process would be conducted as follows:

- Take the flax in small bundles, as it comes from the field or stack, and holding it in the left hand, put the seed end between the threshing machine and the bed or block against which the machine is to strike; then take the handle of the machine in the right hand, and move the machine backward and forward, to strike on the flax, until the seed is all threshed out.

- Take the flax in small handfuls in the left hand, spread it flat between the third and little finger, with the seed end downwards, and the root-end above, as near the hand as possible.

- Put the handful between the beater of the breaking machine, and beat it gently till the three or four inches, which have been under the operation of the machine, appear to be soft.

- Remove the flax a little higher in the hand, so as to let the soft part of the flax rest upon the little finger, and continue to beat it till all is soft, and the wood is separated from the fiber, keeping the left hand close to the block and the flax as flat upon the block as possible.

- The other end of the flax is then to be turned, and the end which has been beaten is to be wrapped round the little finger, the root end flat, and beaten in the machine till the wood is separated, exactly in the same way as the other end was beaten.

Preparation for spinning

Before the flax fibers can be spun into linen, they must be separated from the rest of the stalk. The first step in this process is called retting. Retting is the process of rotting away the inner stalk, leaving the outer fibers intact. At this point there is still straw, or coarse fibers, remaining. To remove these the flax is "broken," the straw is broken up into small, short bits, while the actual fiber is left unharmed, then "scutched," where the straw is scraped away from the fiber, and then pulled through "hackles," which act like combs and comb the straw out of the fiber.

Retting flax

There are several methods of retting flax. It can be retted in a pond, stream, field or a tank. When the retting is complete the bundles of flax feel soft and slimy, and quite a few fibers are standing out from the stalks. When wrapped around a finger the inner woody part springs away from the fibers.

Pond retting is the fastest. It consists of placing the flax in a pool of water which will not evaporate. It generally takes place in a shallow pool which will warm up dramatically in the sun; the process may take from only a couple days to a couple weeks. Pond retted flax is traditionally considered lower quality, possibly because the product can become dirty, and easily over-retts, damaging the fiber. This form of retting also produces quite an odor.

Stream retting is similar to pool retting, but the flax is submerged in bundles in a stream or river. This generally takes longer than pond retting, normally by two or three weeks, but the end product is less likely to be dirty, does not smell as bad and, because the water is cooler, it is less likely to be over-retted.

Both Pond and Stream retting were traditionally used less because they pollute the waters used for the process.

Field retting is laying the flax out in a large field, and allowing dew to collect on it. This process normally takes a month or more, but is generally considered to provide the highest quality flax fibers, and produces the least pollution.

Retting can also be done in a plastic trash can or any type of water tight container of wood, concrete, earthenware or plastic. Metal containers will not work, as an acid is produced when retting, and it would corrode the metal. If the water temperature is kept at 80°F, the retting process under these conditions takes 4 or 5 days. If the water is any colder then it takes longer. Scum will collect at the top and an odour is given off the same as in pond retting. Currently 'enzymatic' retting of flax is being researched as a retting technique to engineer fibers with specific properties (Foulk Akin Dodd (2008). “Pectinolytic enzymes and retting,” BioResources 3(1), 155-169) (Foulk Akin Dodd (2001) "Processing techniques for improving enzyme-retting of flax," Industrial Crops and Products 13 (2001) 239–248).

Dressing the flax

Dressing the flax is the term given to removing the straw from the fibers. Dressing consists of three steps: breaking, scutching, and heckling. The breaking breaks up the straw, then some of the straw is scraped from the fibers in the scutching process, then the fiber is pulled through heckles to remove the last bits of straw.

The dressing is done as follows:

- Breaking: The process of breaking breaks up the straw into short segments. To do it, take the bundles of flax and untie them. Next, in small handfuls, put it between the beater of the breaking machine (a set of wooden blades that mesh together when the upper jaw is lowered, which look like a paper cutter but instead of having a big knife it has a blunt arm), and beat it till the three or four inches that have been beaten appear to be soft. Move the flax a little higher and continue to beat it till all is soft, and the wood is separated from the fiber. When half of the flax is broken, hold the beaten end and beat the rest in the same way as the other end was beaten, till the wood is separated.

- Scutching: In order to remove some of the straw from the fiber, it helps to swing a wooden scutching knife down the fibers while they hang vertically, thus scraping the edge of the knife along the fibers and pull away pieces of the stalk. Some of the fiber will also be scutched away, this cannot be helped and is a normal part of the process.

- Heckling: In this process the fiber is pulled through various different sized heckling combs or heckles. A heckle is a bed of "nails" - sharp, long-tapered, tempered, polished steel pins driven into wooden blocks at regular spacing. A good progression is from 4 pins per square inch, to 12, to 25 to 48 to 80. The first three will remove the straw, and the last two will split and polish the fibers. Some of the finer stuff that comes off in the last hackles is called "tow" and can be carded like wool and spun. It will produce a coarser yarn than the fibers pulled through the heckles because it will still have some straw in it.

Genetically modified flax contamination

In September 2009 it was reported that Canadian flax exports had been contaminated by an unapproved, illegal, genetically modified (GM) variety, known as Triffid. The Flax Council of Canada had raised concerns about the marketability of this variety in Europe and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency had declared it illegal to grow. Despite these precautions the flax crop has now been contaminated with this GM variety, threatening Canada's flax growers, who export 70% of their product to Europe where there is a zero tolerance policy regarding GMOs.[21]

As a symbolic image

Flax is the emblem of Northern Ireland and used by the Northern Ireland Assembly. In a coronet, it appeared on the reverse of the British one pound coin to represent Northern Ireland on coins minted in 1986 and 1991. Flax also represents Northern Ireland on the badge of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and on various logos associated with it.

Common flax is the national flower of Belarus.

In early tellings of the Sleeping Beauty tale, such as Sun, Moon, and Talia by Giambattista Basile, the princess pricks her finger not on a spindle but on a sliver of flax, which is later sucked out by her children conceived as she sleeps.

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Alister D. Muir, Neil D. Westcot, ""Flax: The Genus Linum"". http://books.google.com/books?id=j0zDO165tHcC&pg., page 3 (August 1, 2003).

- ↑ http://www.westonaprice.org/Flaxseed-and-Flaxseed-Oils-for-Omega-3-Fatty-Acids.html

- ↑ Balter M. (2009). Clothes make the (Hu) Man. Science,325(5946):1329.doi:10.1126/science.325_1329a

- ↑ Kvavadze E, Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A, Boaretto E,Jakeli N, Matskevich Z, Meshveliani T. (2009).30,000-Year-Old Wild Flax Fibers. Science, 325(5946):1359. doi:10.1126/science.1175404 Supporting Online Material

- ↑ "Flax nutrition profile". http://www.flaxcouncil.ca/english/index.jsp?p=g3&mp=nutrition. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mayo Clinic (2006-05-01). "Drugs and Supplements: Flaxseed and flaxseed oil (Linum usitatissimum)". http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/flaxseed/NS_patient-flaxseed. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ↑ Alpers, Linda; Sawyer-Morse, Mary K. (1996-08). "Eating Quality of Banana Nut Muffins and Oatmeal Cookies Made With Ground Flaxseed". Journal of the American Dietetic Association 96 (8): 794–796. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00219-2. PMID 8683012.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Malcolmson, L.J. (2006-04). "Storage stability of milled flaxseed". http://www.springerlink.com/content/l544x14m66l05372/. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ Chen, Z-Y. [1] "Oxidative stability of flaxseed lipids during baking"]. http://www.springerlink.com/content/0003-021X].

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of the effects of flaxseed interventions on blood lipids," Pan A, Yu D, Demark-Wahnefried W, Franco OH, Lin X, Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Aug; 90(2): 288-97.

- ↑ Chen J, Wang L, Thompson LU (2006). "Flaxseed and its components reduce metastasis after surgical excision of solid human breast tumor in nude mice". Cancer Lett. 234 (2): 168–75. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2005.03.056. PMID 15913884.

- ↑ Thompson LU, Chen JM, Li T, Strasser-Weippl K, Goss PE (2005). "Dietary flaxseed alters tumor biological markers in postmenopausal breast cancer". Clin. Cancer Res. 11 (10): 3828–35. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2326. PMID 15897583.

- ↑ "Flaxseed Stunts The Growth Of Prostate Tumors". ScienceDaily. 2007-06-04. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/06/070603215443.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/06/070603215443.htm)

- ↑ Am J Clin Nutr (March 25, 2009). doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736Ev1

- ↑ Dahl, WJ; Lockert EA Cammer AL Whiting SJ (December 2005). "Effects of Flax Fiber on Laxation and Glycemic Response in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Medicinal Food 8 (4): 508–511. doi:10.1089/jmf.2005.8.508. PMID 16379563. http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jmf.2005.8.508. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Flaxseed and Flaxseed Oil". National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/flaxseed/. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ WO application 2006137717, Han, Byung-Hoon, Mi-Kyung Pyo, & Eun-Mi Choi, "Edible Flaxseed Oil which Saturated Fatty Acid and Toxic Components Were Removed Therefrom and Preparative Process Thereof", published 2006-12-28

- ↑ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=112726804&sc=fb&cc=fp

- ↑ Wardey, A. J. (1967). The Linen Trade: Ancient and Modern. Routledge. pp. 752. ISBN 071461114X.

- ↑ Illegal GM Flax Contaminates Canadian Exports, Canadian Business, 10 September 2009, accessed 11 September 2009

External links

- North Dakota State University picture comparing flaxseed oil fatty acid content with other oils.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||